Blindsided

Based on a True Story

I went blind once. That’s not something you’ll hear very often, but in 2018 I lost my eyesight completely for about three weeks.

I’ve been dealing with chronic migraines for years. Severe, incapacitating, spirit-destroying migraines. If you’ve never had one, consider yourself lucky. These are not ordinary headaches. Migraines are a full-body ordeal that starts with an acute pain behind the eyes, usually favoring one side of the head. The pain quickly intensifies and before long it feels like someone has plunged an icepick into your skull.

Your whole system starts freaking out in response and things like intense nausea, vertigo, muscle cramps, and fatigue join the party. Adding to the cruelty, migraines tend to linger for hours and sometimes days at a time.

Prodrome

One migraine is too many for a lifetime, and I was getting them three to four times per week. A thing like that takes over your life. You can’t ever really be present. Bad days are abject misery and even the good days are spoiled by exhaustion from the previous episode and the knowledge that another attack is always lurking around the corner. Your relationships, your career, and your quality of life are all held hostage.

In 2016 I finally had the resources to see a specialist about the migraines. I was seen by a neurologist and he ordered all the tests you would expect. MRI, CT scans, blood work. The result: nothing. No tumors, no swelling, no clots or any other obvious thing. So what the hell was going on? For all the wisdom of modern medicine, their guess was as good as mine.

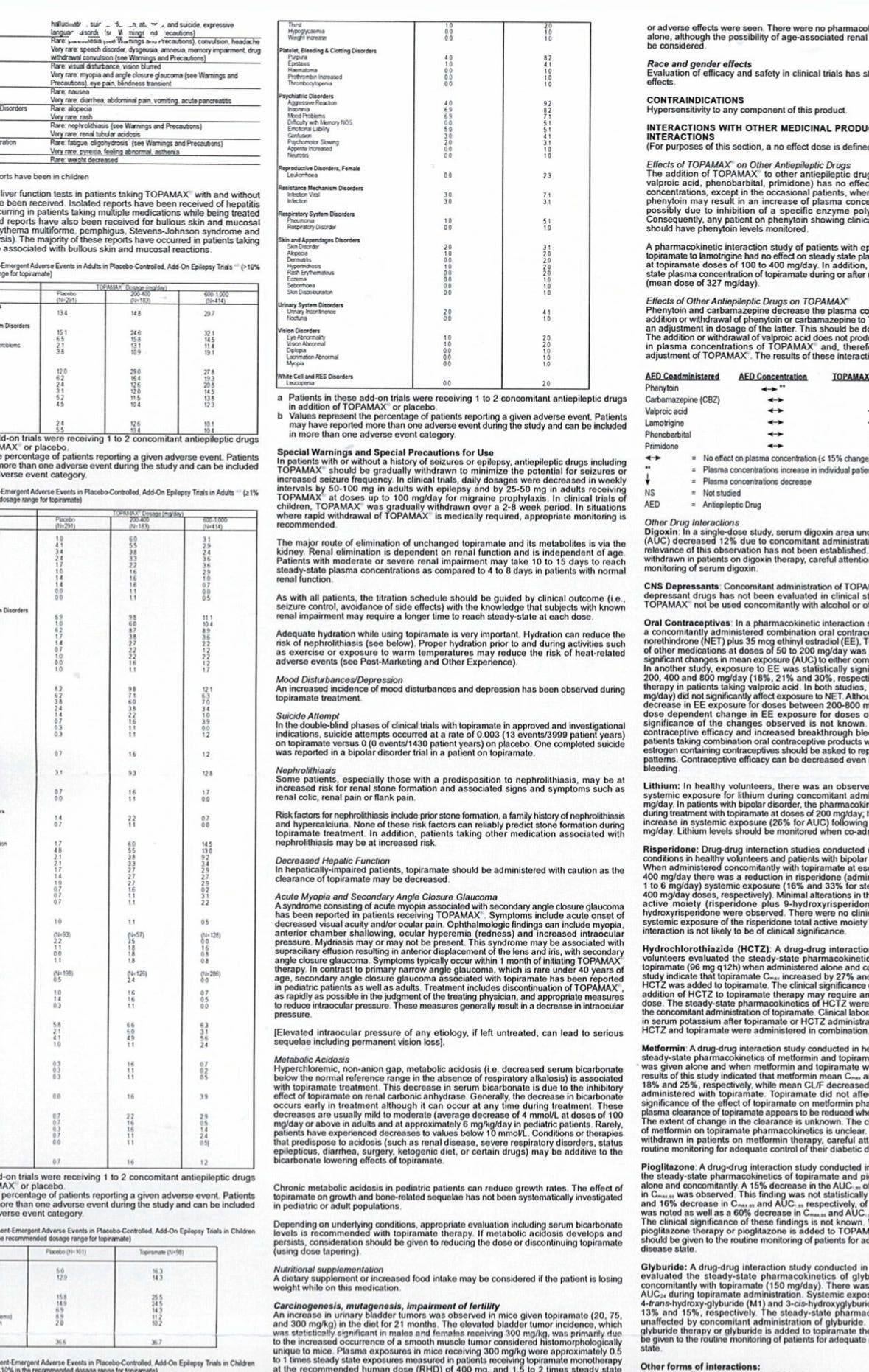

The neurologist considered the situation carefully before throwing some pills at it. When those pills didn’t work, he fell back on his extensive training and threw different pills at it. We went through several rounds of this and none of it helped. In fact, the situation only became worse. The drugs had done nothing for the migraines, but had been very effective at creating their own terrible side effects. Nausea, insomnia, drowsiness, weight gain, you name it. By the time I stopped visiting that neurologist’s practice, I’d cycled through about a dozen heavy duty prescription migraine treatments with no positive results.

Pressure Drop

The situation reached a breaking point when the neurologist wrote me a prescription for a drug called Topamax.

Topamax is a mood stabilizer. Normally prescribed for mental health purposes, it is also sometimes effective as an off-label migraine preventative. At this point, I was just desperate to find some relief, so I tried it.

The instructions for Topamax called for a gradual increase in dosage. For the first week. I would take one pill a day. The second week, two a day. Then the third week I would bump it up to three pills a day and stay there. The first week came and went without any noticeable effect. At the beginning of the second week, I upped the dosage as instructed, taking two pills. When I woke up the next morning, I couldn’t see.

When I tell you that I couldn’t see, I mean it in the most literal sense. I became blind overnight. After allowing myself to panic for a couple of minutes, I was able to calm down enough to figure out getting myself to the emergency room. When I arrived, the doctors on hand were confused. I mentioned the new drug and the neurologist was consulted. They decided that the blindness must be a side effect of the Topamax.

Disclaimer

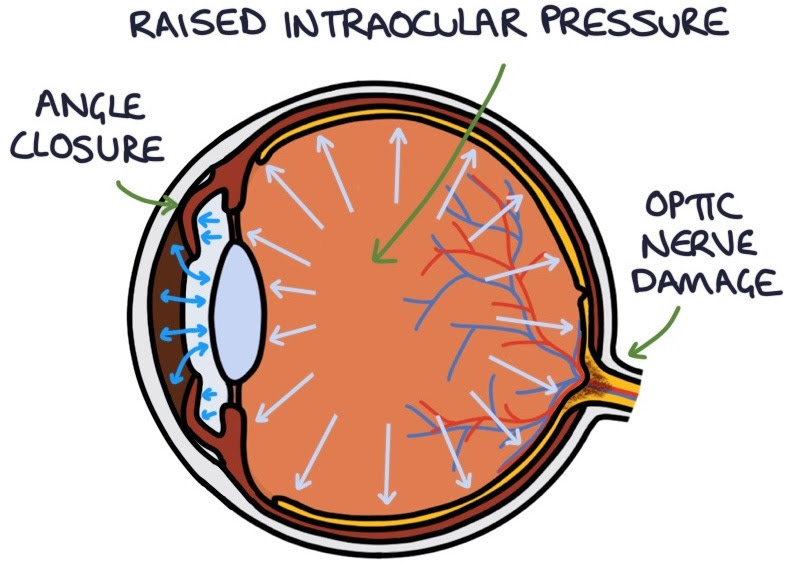

It turns out that in certain rare cases Topamax can induce a condition called Acute Side-Angle Glaucoma. The drug had disabled the valve (or angle) that regulates the fluid pressure in our eyes. Without that release valve, the pressure had increased to about four times the normal amount. This sustained pressure had distorted the lenses of my eyes to the point of blindness, making all but the slightest perception of light invisible to me.

I had become the rare outlier responsible for all of those lengthy disclaimers in prescription medicine ads.

I was given four different eye drop medications to be taken five times a day. These would hopefully reduce the pressure over the course of about three weeks. While I waited and prayed for the drops to take effect, I had nothing to do but sit quietly and contemplate the possibility that my situation might be permanent. At the end of the second week, my eyesight began to partially return. After three weeks had passed I was back to normal. I thank God for that. Of all the things we should never take for granted, our eyes should top the list.

Inward

Looking back on it now, it’s difficult to describe the terror of that initial realization.

I can’t see.

You wake up one morning and your primary means of understanding and interacting with reality is just gone. It’s tough to not have a full meltdown in that moment.

There is no physical sense anyone would ever want to lose. But I think we can all kind of imagine what losing our hearing might be like. Devastating as it would be, you would still at least retain a decent degree of spatial awareness. You would be able to get your bearings. You could take care of yourself for the most part.

Losing your sight is something completely different.

Every action becomes a confusing ordeal. I could do almost nothing. Every movement led to bumping into things at best, and at worst potentially falling and hurting myself. Hundreds of mundane actions that we perform daily without a second thought became frustrating and complex puzzles. I’ve never felt more vulnerable and dependent on others in my life.

Focal Point

My perspective shifted radically after that. I’d had the rare experience of inhabiting the world of the blind. Mercifully, my sight was returned to me after a few weeks, but things haven’t looked the same to me since. Nothing in my life has ever put that kind of fear into me. It forced me to question my priorities and think long and hard about what life really is and how I’d been living it. Introspection becomes unavoidable when looking outward is no longer an option.

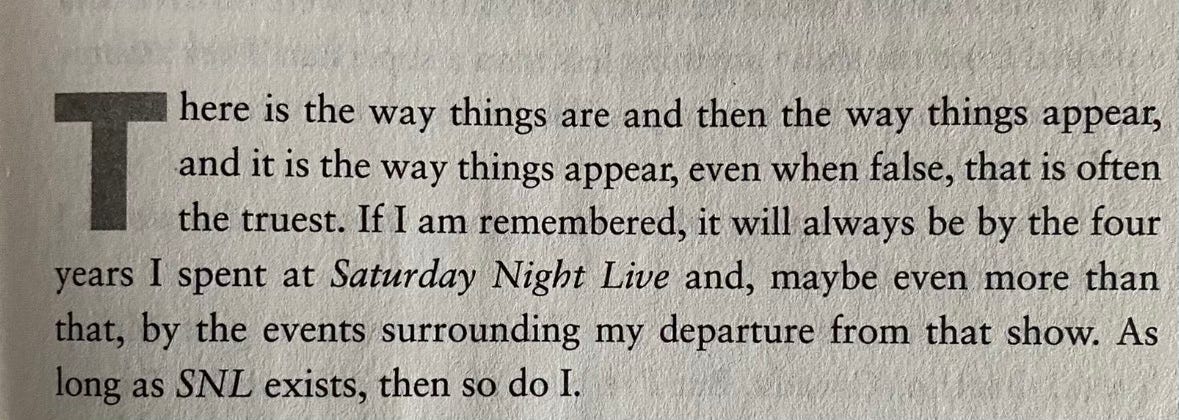

While all of this was going on, I was reminded of a story told by the late comedian Norm Macdonald in his semi-truthful autobiography Based on a True Story: Not a Memoir. In one passage, Norm describes a moment from his childhood, in which a simple exercise led him to question whether a man can ever see things as they truly are.

“Once I learned this truth, I began to see examples of it everywhere. A picture hung on the wall of our parlor. In it, a woman was taking a shirt from a clothesline. She had clothespins in her teeth and it was windy and a boy was tugging at her dress. The woman looked like she was in a hurry and the whole scene gave me the idea that, just outside the frame, full, dark clouds were gathering. But that was not what it was. It was paint. So I decided right then and there to see the picture as it really was. I stared at the thing long and hard, trying to only see the paint. But it was no use. All my eyes would allow me to see was the lie. In fact, the longer I gazed at the paint, the more false detail I began to imagine. The boy was crying, as if afraid, and the woman was weaker than I had first believed. I finally gave up. I understood then that it takes a powerful imagination to see a thing for what it really is.”

-Norm Macdonald

When we look out at the world, what are we really seeing? When Norm describes the artwork he looked at as just “paint”, he is factually correct. That’s all that any painting truly amounts to in the most objective terms. But he’s also correct in saying that it’s nearly impossible for us not to see the young lady, her son, and the shirt flapping around on the clothesline. Our minds will fight to sell us the illusion. Try it for yourself and consider the implications for other parts of our reality.

20/20

A few years later, the events of 2020 turned things upside down once again. This time all of society experienced a massive shift in perspective. The facade we’d all been treating as an agreed upon reality crumbled and fell. The insanity that followed divided the population into three camps:

The first group doubled down and tried to reinforce the illusion.

The second group saw through the illusion, but remained silent and pretended everything was normal.

The third group saw through the illusion and pushed back.

It’s been a rough decade for the third group.

It’s no small thing to have your model of the world fall apart overnight. People and institutions we once trusted and respected showed themselves to be utterly corrupt. Worse, we learned they had been that way for a long time. Maybe forever. The narrators were shown to be unreliable and the truth was laid bare before us. We could finally see the paint.

Riding out the discomfort and uncertainty of those years was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. I know that it was also one of the most important things I’ve ever had to do. Each day felt like a spiritual trial. I know many of you felt that same weight. Refusing to give in to the madness was the only chance any of us had to keep our souls intact. I thank God for seeing so many of us through those awful days.

Things settled down over time, but for my part I’ve been rotating between depression, anger, and apathy ever since.

When most of the people in your life and the institutions of your society expose themselves as being far more vindictive, callous, and corrupted than you ever could have imagined, how the hell are you supposed to just move on with your life?

How can you possibly pretend you didn’t see all of that?

How do you even begin to take any of these people or institutions seriously?

How do you contain your contempt and resentment for all those who joined in the madness?

How can you forgive those who knew it was wrong, but kept their heads down and silently allowed it all to happen?

These are the questions I’ve been wrestling with ever since. It feels like that’s all I’ve been doing. It’s had a paralyzing effect that has made ordinary life awkward and confusing.

It’s difficult to hang out with the neighbors when you know they wished death on people who didn’t comply with the mandates.

Christmas at your uncle’s just isn’t the same after being uninvited a few years ago because of your vax status.

It’s sobering to flip through the contacts in your phone and realize just how little you ever really knew about so many of the people that once filled your life.

Search Party

They say that if you ever find yourself lost in the wilderness, you should try to stay in one place. Remaining stationary prevents you from wandering even further out and making yourself harder to rescue. That’s been the last six years for me. I’ve been stuck in a holding pattern. Waiting for some kind of resolution to it all. Staying in place is sound advice if you’re lost in the woods, but it’s a dead end for those of us trying to navigate the aftermath of the first half of this decade.

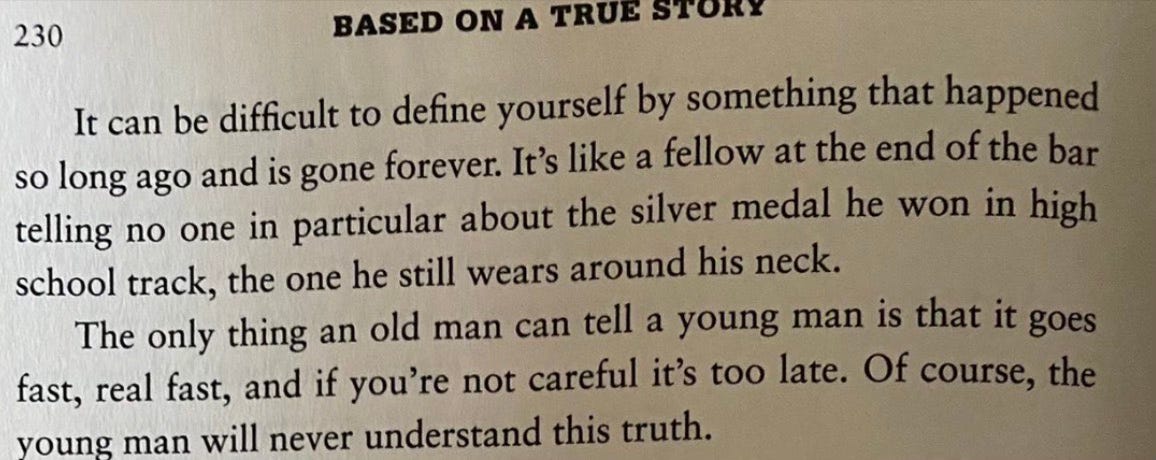

Fine. It’s time to get moving. Where do you even start? In order to truly rejoin the world and move on with my life, I’d have to forget everything I’ve seen and experienced since 2020. I know I can never do that. I wouldn’t want to. I thought about another line from Norm’s book.

There’s how it is and there’s how it appears.

I know how it is, but I’d have to play along with how the world wants it to appear if I’m ever going to carry on with my life.

It isn’t just. It isn’t fair. It just is. I can take that or leave it. The world won’t care either way. Not a satisfying answer but life is rarely cathartic.

There’s no way to ever forget. I know what happened. It matters deeply to me and I will always remember what we all went through. But I can’t let remembering become my whole existence. I’m tired of ruminating. I’m tired of being angry. Most of all I’m tired of feeling stuck.

Long Shot

For my own sake I need to find a way to let go of the last six years of anger, resentment and cynicism. There was a reason for the spiritual trials we all endured. There was a greater purpose to all of it. I don’t believe we made it through all of that just to sit and stew on everything for the rest of our lives.

I have to try sincerely to leave the last few years behind me. I can’t keep living my life in the rearview. I don’t know how many years I have ahead of me, but I want to be able to live them well. To do that, I’ll have to make my peace with the world, as it truly is, and move forward in it.

As Norm would say, “I still have some time before I cross that river.”

I was a boy in the 70s, a youth in the 80s, and a young man in the 90s. I have a vague memory of what that was like, that is perhaps best described as a memory of a memory. The freedom of the ordinary person; the ties of friendship stronger than politics or religion or race; the willingness to live and let live. The vast majority of us had agreed, and that’s how we conducted ourselves, I’m sure of it. I swear I remember that. Maybe I really only remember the feeling of loss when I realized all that was gone. Illusions die hard.

It is difficult to be a human being.

I managed to get past my anger and resentment. But I, like you, will _never_ forget what happened. What was done to us. What people are. What they are capable of when terrorized or enraged. I just tell myself, "Bless them, Father, for they know not what they do."

I spent years trapped in a shell, terrified of everything and everyone. I don't mean after the Madness of 2020 -- I mean my youth. It took me years to get past that, to come out of my shell and be capable of interacting with strangers without discomfort. Alcohol helped.

The Madness took all that away. All the fruits of my efforts. I spent a few more years right back in that shell. I couldn't even go to the grocery store without anxiety. I've since recovered, but life was a numb gray Hell for a while.

I may have let go of the anger, but I'm still guarded in my interactions with others. There is always that unconsious impulse, when encountering a new person: are they one of _them?_